Mindfulness for the Mindfulness-Resistant ADHD Mind

May 9, 2024

Written by: Kelsey Moss, Registered Provisional Psychologist, RYT

In a previous blog post, we talked about Emotional Regulation and ADHD (psst… if you haven’t read it yet, check it out here). As a neurodivergent-affirming psychology practice, we decided to dive into a similar topic of ADHD & Mindfulness!

The term ‘neurospicy’ has been used online as a lighthearted way of talking about those who are neurodivergent. Many neurospicy folks are hesitant about mindfulness. As an ADHD-er myself, I get it! But hear me out and read through to the end of this blog post - it’ll be worth it.

Mindfulness can get a bad rap in the ADHD world and I completely understand why. When your brain is used to following the dopamine, it feels TOUGH and frankly very uncomfortable to sit and focus on the present moment - no matter how hard you try. But we’re going to demystify the use of mindfulness for ADHDers by learning more about the different types of mindfulness and why researchers show that it can be incredibly helpful for neurospicy brains.

First, Let's Unpack More About ADHD

Before we get too far into this, let’s take a moment to make sure we’re on the same page when it comes to Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). There has been a big spike in attention-related disorders in recent years, and whether or not you’ve been officially diagnosed, struggling with ADHD-type symptoms is no joke. ADHD was originally only diagnosed in children, as it was believed symptoms tend to dissipate with age. However, this has changed, especially regarding women with ADHD who typically have a much later onset of symptoms than their male counterparts.

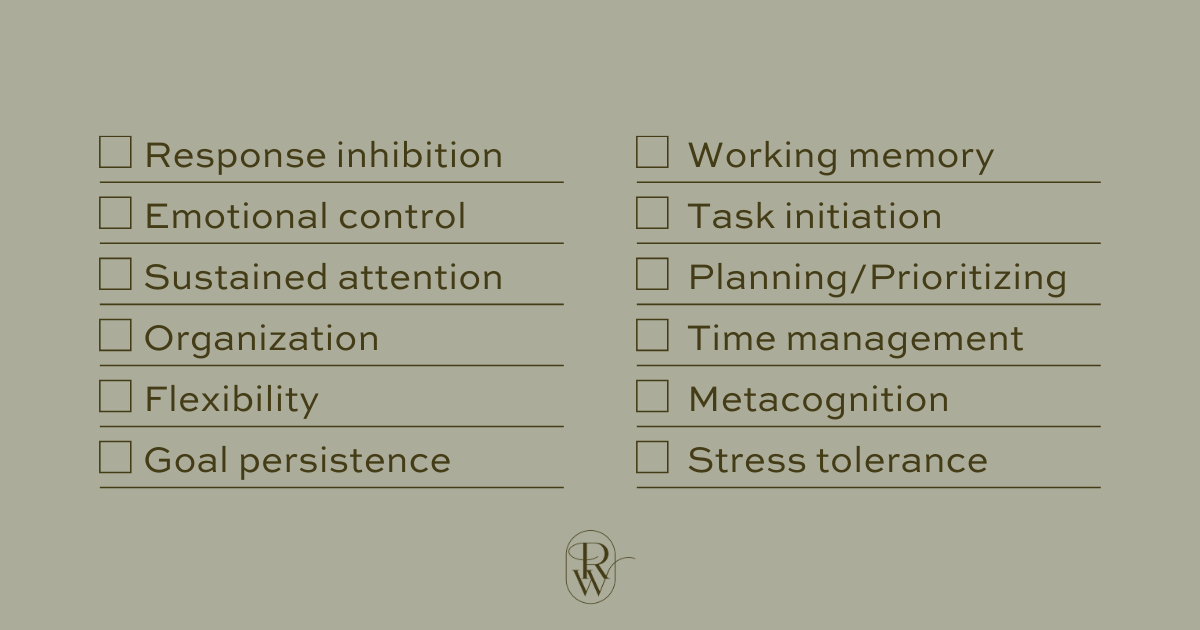

ADHD is diagnosed by mental health professionals using specific manuals, such as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). Although symptoms must be present at the time of diagnosis, there is an additional requirement that at least some symptoms were present in childhood. Common symptoms include limited attention to detail, difficulty with sustained attention, struggling to listen when spoken to directly, disorganisation, and forgetful, among several others. Interestingly, emotional dysregulation and somatic/body-based issues like sensory sensitivities are not listed in the diagnostic criteria, but they are common among those with diagnosed or presumed ADHD. In general, ADHD is characterized by specific struggles in executive functioning skills that limit their ability to function effectively. This include struggles with some or all of the following:

In cases where late diagnosis occurs, it’s also common to fixate on how such a profound diagnosis had been missed growing up. It's completely normal to feel a sense of grief for the younger version of you who struggled for years, often being told you're "too much," "too loud," or "too sensitive." Furthermore, those with late diagnosis tend to develop both helpful and not-so-helpful coping skills. These can be useful, but significant life changes like going to university, moving cities, or becoming a parent might derail you and cause symptoms to become glaringly obvious. It’s not always easy. And if you’re reading this, it’s likely that either you or someone you know has likely felt the heaviness of ADHD.

So with all this in mind, the big question comes down to what we do about it?

Various forms of psychotherapy/counselling, medications, and community/skill-focused interventions have all been shown to help. But with ever-increasing numbers, mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) are being explored as both treatment add-ons and treatment alternatives. As a yoga teacher, therapist, and ADHD-er myself, I am very excited about this!

What actually is mindfulness?

There are many, maannyyy definitions of mindfulness out there, but in general, mindfulness is the practice of focusing your awareness on the present moment, while calmly acknowledging and accepting whatever feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations arise. In simpler terms, it is intentionally experienced awareness. Let’s break this down, shall we?

Intentional: Mindfulness is on purpose. We pay attention to things in our internal and external environments all the time, but that doesn’t mean we’re necessarily practicing mindfulness. When we practice mindfulness, we’re not paying attention by accident; it's intentional.

Experience: Mindfulness is being in a state of observance. We are simply (or not so simply) trying to notice what is happening and be “in the experience.” Instead of trying to control what we're noticing, we become the observer just as though we're watching a film.

Awareness: Let's imagine your attention is a spotlight above a stage. Instead of letting the light control itself and shine all over the place, mindfulness is stepping behind the light and manually directing it to where you want it to be below. Yes, you might have a LOT of things come into your awareness, but that’s good (we'll touch on this below). Usually, we use our five senses to take in information, while our brains process it and place meaning.

Several MBI programs, also known as mindful-based therapies, have been developed for a whole range of issues. For example, MBIs have been found to help cancer patients, those with anxiety and depressive disorders, and most notably, for disordered attention and behavioural concerns. Interventions often include meditation exercises, yoga, breathwork, and assigned homework throughout several weeks.

One reason why MBIs are gaining so much popularity is that there are very few adverse side effects. Beyond the treatment of ADHD and other issues listed above, mindfulness is known to improve other things like self-esteem, relaxation, emotional regulation, attunement, feelings of ease, and more. MBIs are not a “cure,” but they can help improve pressing concerns and when used properly, researchers have found them to be useful in place of or to reduce the use of psychopharmaceuticals. That said, most research is showing that the best treatment outcomes typically result from a combination of interventions.

In terms of mindfulness and the brain, we know that avid mindfulness practices physically change the microscopic structure of your brain through a process called ‘neuroplasticity’. This means that your brain is physically changing based on your experiences. For example, if you learn to play the piano, your brain will physically respond as you learn and pathways will form as your brain practices and remembers this new skill. The more you activate a certain brain network, the more likely it is to be activated again! So as you continue to practice something, it becomes like muscle memory whereby your brain will create space for that experience to physically live somewhere in your brain. We’ll come back to this concept shortly.

Lastly, it’s impossible to NOT mention that these programs, treatments, and therapies all stem from traditional and holistic healing methods practiced in various cultures throughout the world. For instance, many Indigenous healing practices involve tuning into our internal and external worlds with purpose and intention. Furthermore, the practice of yoga is far more than just movement or meditation - it is an entire philosophy and way of living to help reconnect with the most genuine, aligned, and authentic self. Many of these practices were brushed off or looked down upon from a Western medical standpoint, but fortunately, there has been a big push for more holistic and alternative ways of healing. That said, many of these practices are still highly appropriated, though our team at Risewell strives to honour where these traditions have come from while still ensuring we use evidence-based practices as much as possible. We are not perfect, but we are working to be part of the solution.

Types of Mindfulness

Now that we’re all on the same page, let’s discuss two categories of mindfulness and understand why your neurospicy brain may have struggled with mindfulness in the past. Again, mindfulness practices have been used for centuries - they are not new, but many of the categorical labels we reference in this post are relatively new within psychological research.

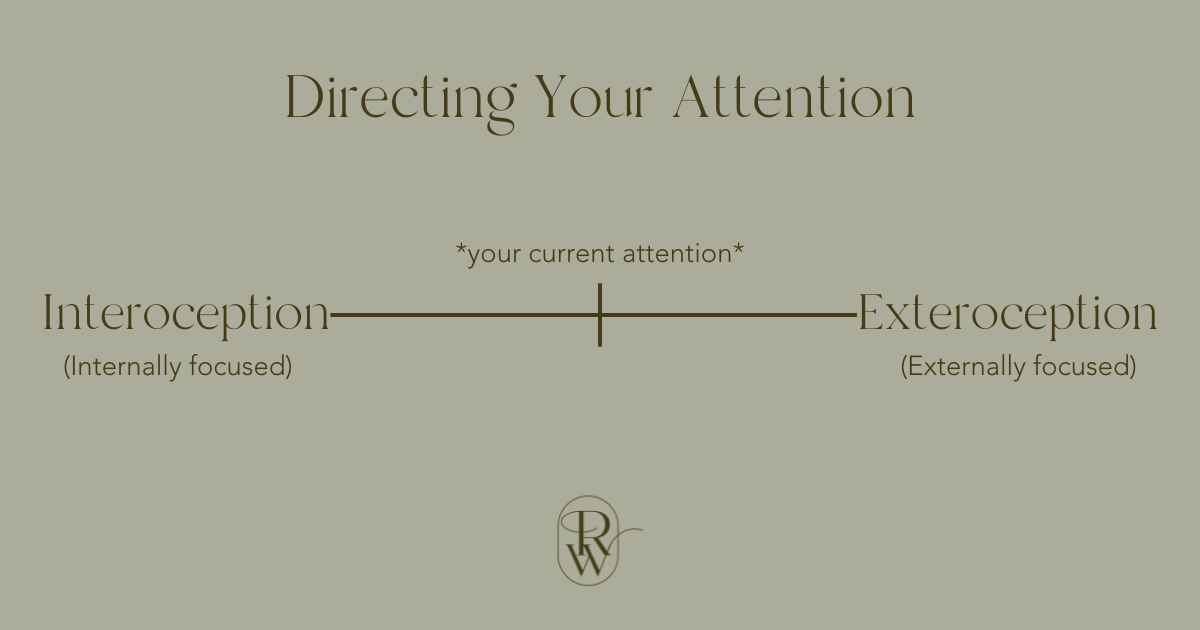

So, let’s imagine that your attention exists on a line (there is much more to it, but for simplicity, we’re going with a line analogy). On one end, you have interoception, which is when your attention is internally focused. Your skin and anything internal count here, such as focusing on your heartbeat, thoughts, breath, movement, feelings, etc. On the other side of the line, you have exteroception, which is anything outside/external to you. This is anything in your environment, such as the distant sounds of vehicles outside, music, the sound of someone else’s voice, the light coming into your window and any shadows it makes, etc. Although in the image below, we place your current attention in the middle, the reality is that where you are on that line shifts around throughout the day (whether you’re conscious of it or not).

When it comes to mindfulness, we are often told to focus our attention internally. But really, we want to be doing the opposite of where we are on that spectrum at a given moment. This goes against what "feels natural" and triggers neuroplasticity, training our brains to better shift our attention on command (psssttt.. ADHDers, wouldn’t that be nice?!). This can be difficult because it goes against what our brains want to do.

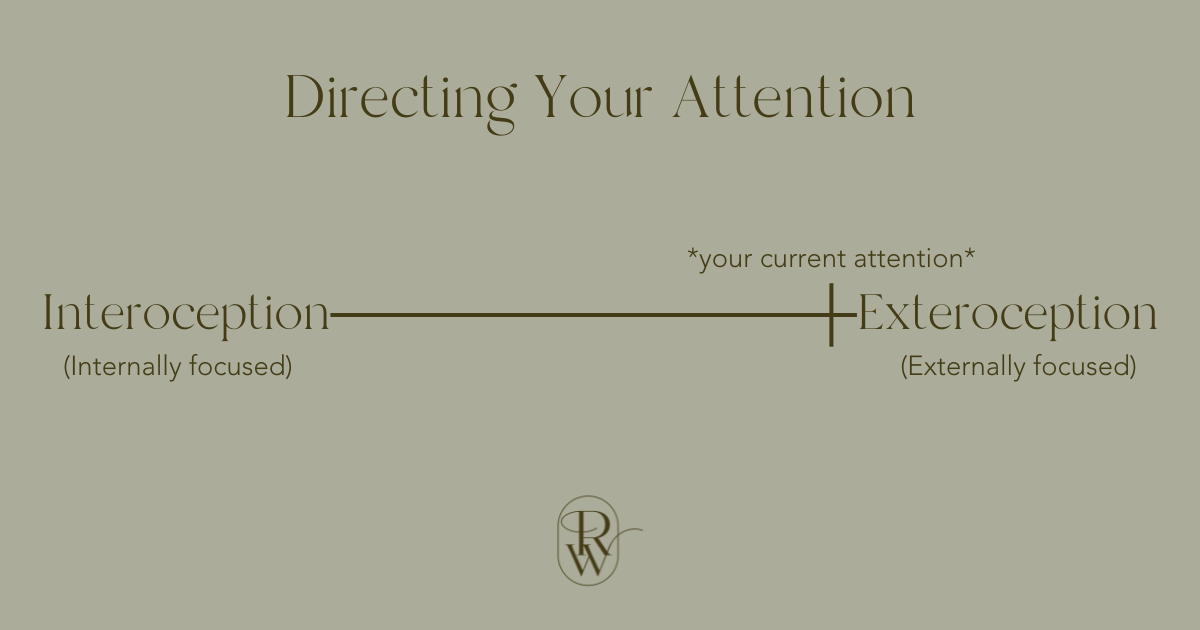

For example, let’s say your attention is currently very close to the exteroceptive side, like this:

Most of our attention would be outside of us in this case. I like to think of this as being in a busy mall on the Saturday before Christmas. There is so much going on around you that your brain is trying its hardest to process and keep up! If you were to intentionally try to add more into exteroceptive attention, you would get dangerously close to your overwhelm threshold (or blow past it completely). Instead, what might help in this moment would be to bring more interoceptive attention in by taking a deep breath, feeling your feet on the ground, or placing a hand on your heart. These are small, but effective ways to shift into an interoceptive mindfulness practice, even if it's just for a brief moment.

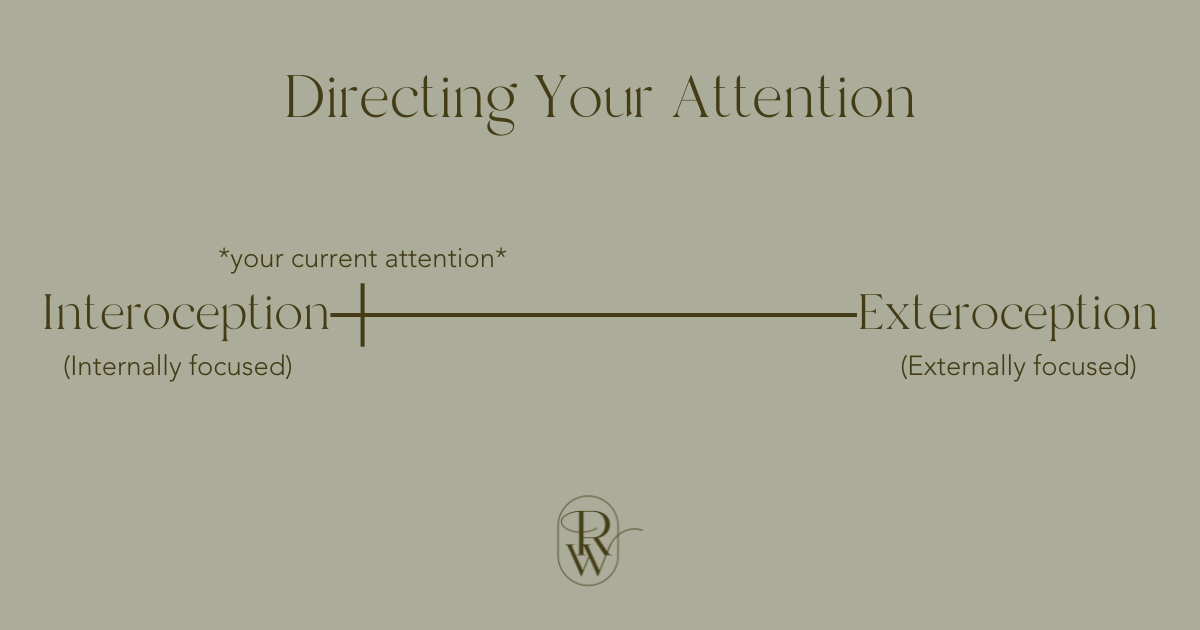

Alternatively, let’s say your attention is already more internally focused, like this:

In this case, your thoughts might be racing, you might be overstimulated by the scratchiness of your sweater, you’re trying to figure out which of your 12 to-do tasks to start on, and you can feel your heart beating faster and faster. Your attention is already very close to your internal threshold. Now at this moment, if someone were to tell you to focus on your breath, it might be too much for your brain to handle at once. In this case, you run a risk of getting overwhelmed and/or shutting down. So if this is the case, which I know many of you neurodivergent folks can relate to, what we ACTUALLY want to do is bring in more exteroceptive mindfulness practices. That could be putting your headphones in and listening to calming music, trying to notice the way the leaves are rustling in the wind outside, or looking at the way the light casts shadows around the room. As simple as it sounds, this type of mindfulness practice is what can help you bring you into a more balanced and grounded state.

As we mentioned before with the brain, the more you practice these, the easier they will get. It's best to practice consistently throughout your days, so when you do get into a tough and potentially overwhelming situation, your brain and body already know what to do.

Let’s touch on a few important caveats:

Trauma. Trauma primes our brains to search for both internal and external signs of danger. If we have spent several years avoiding our feelings, going inward can be very distressing. This is partly because there is so much going on, that once we open the faucet, we don’t necessarily know how to turn it off. Similarly, our brains might also be hypervigilant about our external surroundings because they are trying to protect us from harm. We might be hyper-aware of small shifts in people's moods or interpret someone's very neutral behaviours as a threat (even when they’re not). Trauma alters our brains to work in ways that value safety over everything else. This could also mean that if we don’t have what it takes to hold space for the heaviness of our pain, we might dissociate, distract, or avoid. This is why it's so important to bring both types of mindfulness into your life to slowly and steadily teach your body how to foster control.

Meditation & Altered States of Consciousness. Some forms of mindfulness or meditation are designed to bring you deep into an interoceptive state, taking a judgement-free and intuition-focused approach. Although these can be incredibly transformative experiences, it can take time to train our brains that we’re safe enough to go so far inward. Before we get to this stage, it’s important to first learn how to better control our attention before we start trying these practices. So to my fellow ADHD folks who struggle to sit for more than 30 seconds in meditation, that’s A-Okay! There’s a reason we call them practices - it’s a lifelong pursuit.

ADHD Brains and the Struggle of “Being Present”. It probably doesn’t come as a surprise when we say that those with ADHD struggle to direct their attention. However, in terms of interoception and exteroception, there are neurological differences between these two types of awareness. Researchers are starting to realize that those who struggle to “be present in the body” typically have brains that process information differently. More specifically, the ability to “be present” is largely dependent on the interaction between how your brain processes exteroceptive input and your ability to activate the interoceptive networks in the brain! Again... practice, practice, practice!

Neuroplasticity and Mindfulness. This is a big one. Most people who struggle with mindfulness report that they try to quiet the mind, but they can't help the seemingly endless string of random thoughts that continually pop up! If this is the case, there is a misconception about what they think “practice” is. What actually triggers neuroplasticity in the brain is not the moments where your mind is supposedly "quiet." Interestingly enough, neuroplasticity occurs when you NOTICE that your mind has wandered and intentionally, without judgment, bring your awareness back. Your brain is wired to think, so having random thoughts come up is normal! It means your brain is doing what it is supposed to do. However, if we want to build our attentional skills, then we need to shift our idea of mindfulness and recognize that it’s a “good” thing when you notice your brain is wandering, it means you get an opportunity to rein in your attention and build up that skill.

The more you practice both interoceptive and exteroceptive mindfulness, the more your brain will understand how to shift your attention like muscle memory.

All in all, we want to emphasize that your brain is beautifully unique, and not something to “fix.” Being neurodivergent means that your brain truly does work differently - and that’s okay!!!! That said, sometimes we need to do things we don’t want to do, and incorporating mindfulness into your life can be an excellent way to start. Our final note on this topic is that you don’t need to sit and meditate for an hour a day to benefit from a mindfulness practice. Sometimes the best way is to start small, notice where on that continuum you are, and make small attentional shifts to help your brain feel more at ease.

If you want to start building up a more comprehensive mindfulness practice and don’t know where to start, reach out to our Risewell Team and book a consultation today.

References:

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder [Pamphlet]. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/educational-resources/dsm-5-fact-sheets

Bakrater-Bodmann, R., Azeveda, R. T., Ainley, V., & Tsakiris, M. (2020). Interoceptive awareness is negatively related to the exteroceptive manipulation of bodily self-location. Front. Psychol., 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.562016

Cairncoss M., & Miller C. J. (2016). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapies for ADHD: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(5), 627–643. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715625301

Collins, S. (2018). Culturally responsive and socially just counselling: Teaching and learning guide. Faculty of Health Disciplines Open Textbooks, Athabasca University.

Dawson, P., & Guare, R. (2008). Smart but scattered. Guilford Publications.

Goodwin, K. A., & Goodwin, C. J. (2017). Research in psychology: Methods and designs (8th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Haydicky, J., Shecter, C., Wiener, J., & Ducharme, J. (2015). Evaluation of MBCT for adolescents with ADHD and their parents: Impact on individual and family functioning. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 24(1), 76–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9815-1

Hofheinz, C., Reder, M., & Michalak, J. (2020). How specific is cognitive change? A randomized controlled trial comparing brief cognitive and mindfulness interventions for depression. Psychotherapy Research, 30(5), 675–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1685138

Hoxhaj, E., Sadohara, C., Borel, P., D, A. R., Sobanski, E., Müller, H., Feige, B., Matthies, S., & Philipsen, A. (2018). Mindfulness vs psychoeducation in adult ADHD: A randomized controlled trial. European Archives of Psychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience, 268(4), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-018-0868-4

Kassab, R., & Alexandra, F. (2015). Integration of exteroceptive and interoceptive information within the hippocampus: a computational study. Front. Syst. Neurosci., 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2015.00087

Levit, D. (2018). Somatic experiencing: In the realms of trauma and dissociation — What we can do, when what we do, is really not good enough. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 28(5), 586–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/10481885.2018.1506225

Lo, H., Wong, S., Wong, J., Yeung, J., Snel, E., & Wong, S. (2020). The effects of family-based mindfulness intervention on ADHD symptomology in young children and their parents: A randomized control trial. Journal of attention disorders, 24(5), 667–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717743330

O’Brien, V., & Likis, W. E. (2020). Client experiences of mindfulness meditation in counseling: A qualitative study. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 59(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/johc.12127

Palacios, A. F., & Lemberger, T. M. E. (2019). A counselor‐delivered mindfulness and social–emotional learning intervention for early childhood educators. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 58(3), 184–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/johc.12119

van der Oord, S., Bögels, S. M., & Peijnenburg, D. (2012). The effectiveness of mindfulness training for children with ADHD and mindful parenting for their parents. Journal of child and family studies, 21(1), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9457-0

Vonderlin, R., Müller, G., Schmidt, B., Biermann, M., Kleindienst, N., Bohus, M., & Lyssenko, L. (2021). Effectiveness of a mindfulness- and skill-based health-promoting leadership intervention on supervisor and employee levels: A quasi-experimental multisite field study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000301

Young, S., Adamo, N., Ásgeirsdóttir, B. B., Branney, P., Beckett, M., Colley, W., Cubbin, S., Deeley, Q., Farrag, E., Gudjonsson, G., Hill, P., Hollingdale, J., Kilic, O., Lloyd, T., Mason, P., Paliokosta, E., Perecherla, S., Sedgwick, J., Skirrow, C., Tierney, K., … Woodhouse, E. (2020). Females with ADHD: An expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in girls and women. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 404. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02707-9

Zuo, Z. X., Price, C. J., & Farb, N. A. S. (2023). A machine learning approach towards the differentiation between interoceptive and exteroceptive attention. European Journal of Neuroscience, 58(2), 2523–2546. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.16045